Ba was born on February 22, 1973.

He was the youngest child of four. He was born into a family of Chinese peasant farmers. His parents were 陈厚珍 (Chen Hou Zhen), my grandfather, and 郑国霞 (Zheng Guoxia), my grandmother. They were third-generation cousins; they did not love each other. They were in an arranged marriage and could barely stand each other towards the latter half of their lives. Neither were perfect parents. By Western standards, they would be considered abusive. But in the rural village that Ba grew up in, no CPS existed. In the rural village that Ba grew up in, he had nothing.

His childhood was confined to the small village in 太平乡, the Peace and Harmony District in Hubei province. His only connection to the outside world was his richer friend’s radio and his imagination, but outside of that, his world was small.

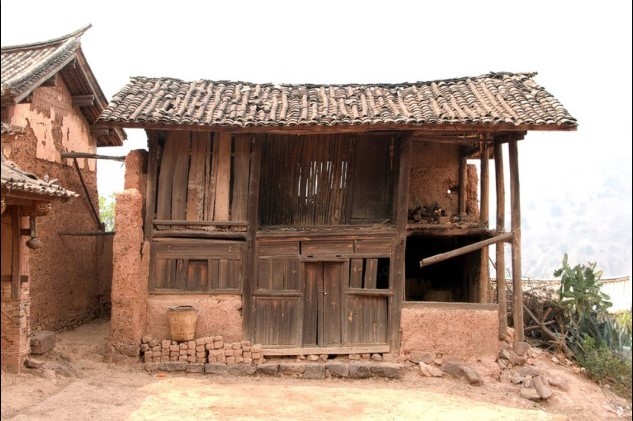

When my dad talks to me about his village, his voice trails off. His eyes look into an unending distance. He goes somewhere into his own memories. I have to be gentle with my voice, gentle with my questions, gentle with my curiosity. Because every time I ask him to recount another memory from his time in 太平乡, I’m asking him to return to a place that is still vivid in his memories: a small mud hut with a single bamboo bed. I’m asking him to play as a representative of 1970s China while I play anthropologist, interviewing him and cataloging the memories of his childhood. I’m asking him to uncover and dust off a part of himself that most immigrant parents keep locked inside of them.

If I’m an anthropologist and Ba is the representative, this paper is our archive.

Through his stories and our interviews, I’ve begun to catalog a series of objects from his childhood that are deeply tied to his memories of the village. I’ve researched the history behind these objects and his stories. I’ve discovered two articles of clothing and three objects of discipline so far. From the hand-me-down collared shirt and collared shirt, I hope to shed light on how the people of post-1970s China used clothing to express political allegiances and the tumultuous political climate of the time. From the cloth shoe, the bench, and the rock, I hope to show how the Chinese family was structured, how Chinese parents used corporal punishment to discipline their children, and how the legal structure failed to protect China’s most vulnerable. In short, I hope to explore what it was like to grow up in the rural villages of China post-1970s in a post-Maoist, Open Door Policy era from both the personal and the historical perspective.

Welcome to our archive.

Thank you for reading A Family and Country’s History Part 2 by Amanda Chen! Stay tuned for more works by Amanda in the future and read more about her here. The third part of A Family and Country’s History is scheduled to be published next Friday, July 8th, 2022.